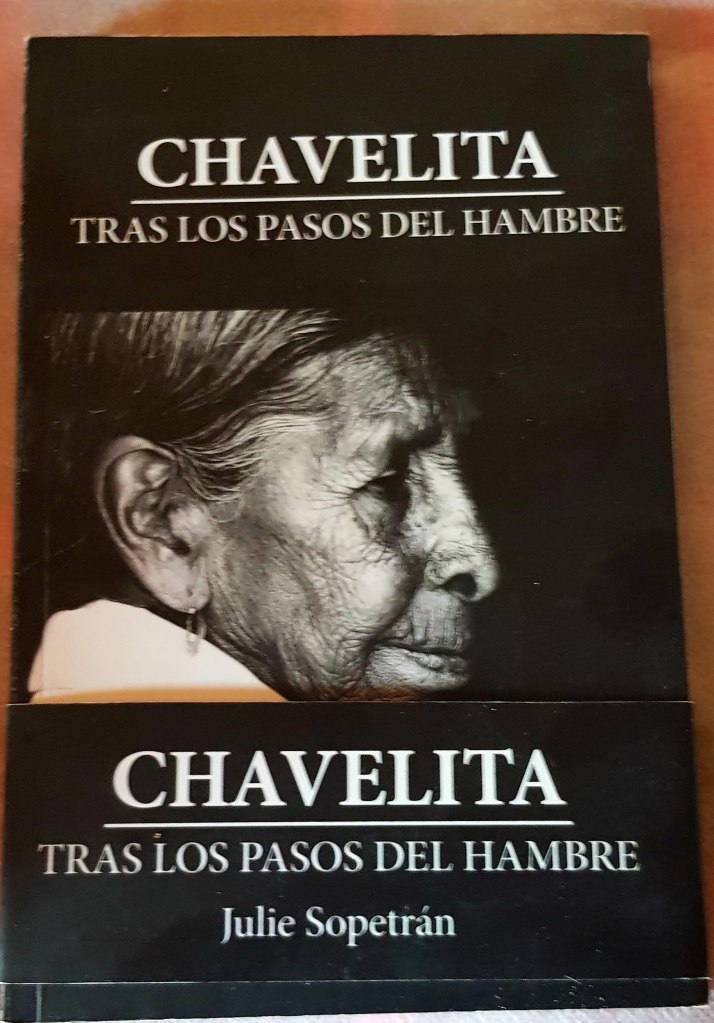

CHAVELITA (Libro. Español – Inglés)

CHAVELITA

CHAVELITA

TRAS LOS PASOS DEL HAMBRE

ON THE TRAIL OF HUNGRY

HISTORIA ORAL

Libro de Julie Sopetrán

Dedicatoria:

A Lucy Pompa, con mucho cariño, quien un día

me escribió para preguntarme por su bisabuela...

y también para su familia.

INDICE

UNAS PALABRAS

UNA PEQUEÑA REFLEXIÓN – Julie Sopetrán

MAPA ITINERARIO DEL RECORRIDO DE ISABEL ANDANDO CON PANCHO VILLA

Capítulo 1 LOS PRIMEROS AÑOS EN LA HACIENDA

Don Porfirio

Vida de Isabel en la hacienda

Vida familiar

Noviazgo con Marcelino Amezquita

Capítulo 2 EVOLUCIÓN Y TIEMPOS DIFÍCILES

Madero

Las guerras de la muerte

Carranza y Villa: estudios en blanco y negro

La Retirada

Capítulo 3 VIDA DE ISABEL EN LA TIERRA SOÑADA

Marcelino, su enfermedad y muerte

Notas de curanderismo y brujería

Los trabajos y los días de Isabel

Reminiscencias

Capítulo 4 LOS AÑOS DE ISABEL EN CALIFORNIA

Lo que hace ahora

Dios y el demonio

Capítulo 5 EL LEGADO DE RAMÓN VÁZQUEZ

Epílogo Loa a Isabel. Poema de Julie Sopetrán

Mapa itinerario del camino que siguió Isabel.

UNAS PALABRAS

La vida de Isabel Amezquita comienza con un poco de ironía, debido a la mala información que dieron sus padrinos en la Iglesia al bautizarla. Sus palabras me dejan pensando…

«Fíjese, yo agarré nueve años al siglo. Nací en Santa María, otra tiendita cerca de la Hacienda de Castro (en el Estado de Jalisco) México. La hacienda era de un general que se llamaba Juan Castro. Desde Santa María a la Encarnación de Díaz, había siete leguas de retirao. Pero yo tengo aquí un papel que le voy a enseñar donde dice cuando yo nací…»

Encarnación de Díaz está localizado en las tierras altas del Estado de Jalisco. Su riqueza consiste en la agricultura y el ganado vacuno. El campesino trabaja duramente debido a que la tierra no es muy fértil. Allí se produce trigo, maíz, fruta, olivos y magüeyes. La Encarnación está cerca de Guadalajara y Aguas Calientes.

Isabel mira entre uno de sus bolsos y saca un papel escrito a máquina que dice lo siguiente:

«El párroco que suscribe, certifica en debida forma que: en el libro de bautismos número 50 y la hoja 128, existe un acta que dice: Al centro.

En la Iglesia Parroquial de La Encarnación a veintidós de Noviembre de mil ochocientos noventa y uno. Yo el Presbítero Don Pedro Pérez, con licencia del actual párroco, bauticé solemnemente y ungí con el Óleo y Crisma Sagrados, a una niña de cuatro días, nacida en Santa María, a las ocho de la mañana a quien puse por nombre Exiquia, hija legítima de Vicente Vázquez y de Teresa Limón; abuelos paternos Juan Vázquez y Nazarea Hernández; los maternos, Miguel Limón y Micaela Ponce; padrinos, Margarito Magdaleno a quien advertí su obligación y parentesco espiritual. Y lo firmamos Felipe Ramírez-Pedro Pérez (Rúbricas) Es copia fiel del original. Encarnación, Jalisco 18 de Junio 1969. El Párroco.»

Isabel, tiene algo que decirnos acerca del acta anteriormente transcrita. Pero antes de empezar su explicación me enseña una carta de su hermano que dice entre otras cosas:

«Enero, 21, 1962

Mi inolvidable y apresiable hermana:

Encontré tu carta de nacimiento del Sr. Cura Joel S. Delgado, Notaría Parroquial de Encarnación de Díaz, Estado de Jalisco, México, y copio dicha carta que dice así: «Registré cuidadosamente el acta de Bautismo de su nombre, Exiquia Vázquez, mismo que encontré el 22 de Noviembre 1891″ Naciste el día 10 del mismo mes de Noviembre y el nombre tuyo es como dice, o sea Exiquia…»

Por lo que hay una confusión. Al preguntar a Isabel acerca de la fecha exacta de su nacimiento, pues ella siguiendo los datos fieles a la copia del acta transcrita anteriormente, dice que nació cuatro días antes del 22 de Noviembre… «bauticé a una niña de cuatro días». En ese caso cuatro días antes del 22 de Noviembre, es el día 18 de Noviembre. Y no sabe por qué su hermano dice que nació el 10 de Noviembre. Isabel dice: «Pues no sé. Pero yo creo que nací el 18 de Noviembre, como dice el cura. Creo que mi hermano estaba equivocado». Por esta confusión Chavelita se siente enojada. Le pregunté por qué el nombre de Exiquia y de dónde le vino el de Isabel.

«Pues mire… ¿Sabe lo que le digo? Que yo creo que mis padrinos estarían borrachos, todo lo dieron mal. En México, era costumbre que la madre se quedara en la casa y no fuera a los bautizos, sólo el padre. Mi padre dijo que me llamaran Isabel, como mi madre. Los dos estaban de acuerdo y mi nombre es Isabel y no Exiquia o María Eziquia, como dicen muy mal dicho. Mis padrinos eran buena gente. Yo tuve dos padrinos: Luis Villanderos y Margarita, su hija. Era un señor viudo que vivía en el rancho con varias hijas, pero toda la información la dieron mal. Esta señorita Margarita, era soltera y nunca se casó, oiga, nunca.»

«Así me pusieron ellos, todo equivocado, pues mi madre se llamaba Tomasa y ahí ponen Teresa. Y no es Teresa, mi madre es Tomasa Limón. ¿Y sabe? ¡No me sirven estos papeles! Todos son falsos y están mal. Fui a reclamar eso porque me bautizaron con mentiras, oiga, sí. ¡Con mentiras! Mis padrinos hicieron todo mal y ahora todo eso es falso. ¿Qué le parece?»

Pues me parece muy mal, Isabel. Muy mal.

JSopetrán

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

Una pequeña reflexión

Esta es una historia tan universal como particular. Es la historia de una mujer mexicana, campesina, cuya lucha individual viene a representar, la lucha común de las innumerables mujeres del pueblo mexicano que han sobrevivido siglos de adversidades, desde la conquista a la colonización, desde el absolutismo a la revolución. Esta es la historia gráfica, oral, de lo que observamos en las pinturas de Orozco. La historia de la mujer metida en su rebozo. Siempre en pié de la marcha. Caracterizada sobre todo por la pobreza y el sufrimiento. Esta marcha es, sin embargo, la marcha del movimiento que va adelante, marcada por la fe y el valor de sus raíces.

Isabel Vázquez de Amezquita, a los ochenta y ocho años de edad, hace que este movimiento sea específico y particular. Ella es consciente del significado de su historia, no por haberla vivido ella sola, sino por haberla vivido con todo su pueblo.

«Muchos pasaron por esto» dice con una voz fuerte y veraz. Y por ello, su historia tiene implicaciones profundamente universales, históricas.

Pero aquí no tenemos sólo a una heroína, Isabel no es una de esas mujeres que tomaron parte activa en la revolución mexicana, no fue una de esas mujeres que montaban a caballo y disparaban tan bien como cualquier hombre. Ella es una de esas mujeres cuidadoras del maíz, ella entraba a la revolución con sus metates de piedra en las espaldas. Ella cocinaba, barría, limpiaba, vivía de cualquier manera mientras sus hombres soportaban los esfuerzos y las luchas siguiendo a los guerrilleros. Ella fue una mujer del silencio. Fue una mujer valiente, molinera del maíz que daba luz a los caminos y alimento a los hombres rotos por la guerra.

De recién casada, Isabel siguió a su marido, obrero de una hacienda, se unieron a las filas de las tropas de Pancho Villa. Porque Villa controlaba los ferrocarriles del Norte y, por consiguiente, necesitaba obreros que reconstruyeran los ferrocarriles destrozados por los carrancistas. Por cuatro años, desde 1915 hasta 1919, Isabel y su marido Marcelino, vivieron una vida miserable, sin casa, siempre caminando, corriendo y escapando y pasando hambre.

Chavelita, me cuenta que ella dio vida a su primera criatura en una cañada, al mismo tiempo que iba a empezar una batalla entre los villistas y los carrancistas. Después, la criatura ya ciega, porque sufrió un ataque de viruela, murió de hambre así como los demás niños de Isabel, que nacieron por aquellos caminos.

Mientras la historia habla de las pérdidas de una mujer (pérdidas de hijos, padres, hermanos, patria) su tema central es el triunfo de la supervivencia.

He de destacar que Isabel nunca se rindió ante la lucha. Continuó trabajando y criando a sus nuevos hijos, fue una madre valerosa en la marcha adelante de la revolución, con sus pies plantados firmemente en la tierra, con sus ojos raramente mirando al cielo. Ella no teorizaba lo abstracto, vivía la realidad, la sentía, la ratificaba.

Isabel percibe el mundo en un plano claramente definido, donde la persona humana tiene o no tiene que comer, trabaja o no tiene la oportunidad de hacerlo, si es así entonces es cuando sus hijos se mueren de hambre. Siempre mira el trabajo como una oportunidad. Estas son las realidades extremas que vienen a formar sus creencias. Lo demás no importa demasiado o no tiene consecuencia en la vida, excepto, su creencia en Dios.

Llegar a los Estados Unidos, la salvó del peligro de morir a balazos en la revolución mexicana. Para el inmigrante no le es fácil buscarse la vida. Ella da las gracias por la ocasión que tiene de trabajar para alimentar a sus hijos.

Cuando Marcelino Amezquita cruzó el Río Grande por El Paso, él llevaba su corbata bien atada, el símbolo de su dignidad y su deseo de trabajar. Isabel lo siguió, iba apretando a su pecho un niño moribundo. Y esto era todo lo que llevaban de Juárez. La corbata de Marcelino y el hijo agonizante, ambos, eran el símbolo de urgencia de sobrevivir y el deseo de trabajar.

Y lo hicieron, por casi veinte años trabajaron duro y mejoraron socialmente. Tuvieron más hijos. Tres sobrevivieron. Luego, Marcelino enfermó y murió. Isabel quedó sola para trabajar, para llevar la carga ella misma, ella sola. Así lo dice con fuerza: «Es la carga», se ríe con su acostumbrado buen humor… y me dice:

«Todo esto hace al burro que siga caminando».

Es muy importante notar que esta historia no se marca solamente con la tristeza, sino también con el buen humor de Isabel. Ella es consciente de sus pérdidas, pero también es consciente de sus triunfos.

Estos triunfos incluyen una progenie semejante que son quienes la quieren y la veneran.

Además de sus tres hijos, que ya tienen sus sesenta y tantos años, Isabel tiene muchos nietos, biznietos y tataranietos. Tantos tiene, confiesa con orgullo, que a veces pierde la cuenta.

Su nieta Lucy es la más devota, me dice, Lucy que también es abuela. Y además de sus hijos y nietos, Isabel tiene un buen círculo de amigas, mujeres inmigrantes como ella, quienes pasan el tiempo charlando del pasado. Bromean y hacen chistes del pasado entre ellas y, a veces se ponen a rezar como si todas adoraran a un mismo Dios.

Al estar alrededor de Isabel, con sus amistades y con sus hijas y nietos, en ese espacio, se siente la afirmación de la vida. Una empieza a conocer nuevas razones para sobrevivir. Se desarrollan los nuevos valores y se empieza a tener un poco más de fe en la providencia. Yo en Chavelita encuentro una gran inspiración frente al Arte de la Verdad. He conservado en esta historia su propio lenguaje, su manera de ser y estar, de decir y hacer y así siento con ella y con sus sentimientos, sus buenos sentimientos, luz de una presencia que renueva el ambiente y lo limpia.

Por ley de vida, pronto, ella saldrá de este mundo, pero cuando se vaya, todos, vamos a ser sus herederos, esa herencia tan rica, de haberla conocido, de haber hablado y compartido con sus palabras, su propia vida.

«Me voy a morir al año que entra» – Me dice sonriente.- «Acuérdense que se lo he dicho este día. Mi cabeza me dice que ya no debo estar aquí, pero yo le digo a esta cabeza mía que se espere un ratito más»

Se ríe. Su rostro resplandece de alegría. Y su risa no tiene edad.

Julie Sopetrán

Redwood City, California 1978-79

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

Capítulo 1

Los primeros años en la hacienda

Isabel, nació en una época muy importante para su país. Ella nació un año después que Porfirio Díaz, el gran dictador militar que expropió la tierra y dictó la ley de 1894, favoreciendo a la aristocracia y dejando al pueblo en la completa miseria.

En 1910, un total del 96% de las familias rurales no tenían ninguna propiedad. Lo indígenas mexicanos se quedaron sin tierras y sólo los ricos se apropiaron de estos bienes que no les pertenecían. Aproximadamente diez millones de indígenas (la tercera parte de la población) perdieron sus bienes y vinieron a ser siervos y criados de los grandes propietarios. Pero los errores de Porfirio Díaz, no sólo fueron de esta índole. La educación rural fue completamente abandonada, ignorada por el gobierno.

En 1910, el 80% de la población mexicana era analfabeta. La Iglesia se benefició con este gobierno, los extranjeros adquirieron beneficios, pero el pueblo de México, sufrió las consecuencias de esta Corporación de los llamados «Científicos», como llegó a ser el gobierno de Díaz.

Isabel nació bajo esta dominación militar, creció, pasó su infancia sin escuela rural, sin educación, esa educación a la que tenía todo derecho.

Ella me dice en su entrañable lenguaje:

«Pues no fui a la escuela, no sé leer. Mi hermano sí aprendió a leer muy bien, pero yo no. Allí en el rancho no había escuelas, no había profesores, no había nada de eso…»

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

Don Porfirio

Y ella también me habla de Don Porfirio.

«Sí. Porfirio fue dictador durante 34 años. ¿Pero sabe lo que le digo?

Que no era malo, porque cuando él estaba en el gobierno, había mucha comida y mucho trabajo para todos y en México hay mucha hambre. El que la tiene la come y el que no la tiene no la come. Porque los hambrientos no ayudan a los demás, los que tienen tampoco ayudan y Porfirio Díaz daba comida».

No. Isabel no entiende de gobiernos ni de políticas, ni de historias que ella no haya vivido. Para ella los libros son algo importante, pero no los puede leer. Sólo recuerda lo que le contaban sus abuelos.

«Yo recuerdo que mi abuelo me decía, y también lo decían otros hombres trabajadores, que Porfirio Díaz, era un soldao mexicano que nació en el Estado de Oaxaca, su familia era pobre y su madre tenía algo de indígena, los curas fueron los que le educaron pero no se más. Cuando yo estaba en mi casa, con mi padre y mi madre, conocí a Porfirio Díaz en persona y fue en La Encarnación, porque él vino, y era bueno, y salimos a recibirle y recuerdo que nos decía: «Adiós». Y le digo que este era un tiempo cuando los trabajadores cobraran un peso por semana y entonces todo estaba barato. Traíamos a casa un centavo de aceite, y ahora no. Todo está muy caro. Pero le hablo de cuando Porfirio Díaz iba a visitarnos en tren.»

Isabel ríe, aprieta sus manos, yo la escucho con atención. Mi curiosidad aumenta he de comprobar si es cierto lo que me dice Isabel, para poder escribirlo.

Y sí, a la edad de 15 años Porfirio entra en el Seminario Pontifical de Oaxaca. En 1849, siguiendo la influencia de Benito Juárez, rector de la universidad, cambió sus ambiciones clericales y estudió leyes con Juárez, en el Instituto de Artes y Ciencias. Sin duda era un hombre de acción y durante la guerra con Estados Unidos en 1847-48, dejó su casa y sirvió a la Armada.

Díaz soportó a Juárez en las medidas anticlericales de la Constitución de 1857. Él se opuso a la invasión francesa de 1862 y defendió el ataque francés de Puebla. Más tarde, fue candidato a la presidencia del gobierno en contra de Juárez y de Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. Fue elegido presidente en mayo de 1877. Sus métodos fueron demasiado fuertes a veces, otras, con resultados satisfactorios para México, como en las relaciones con otros países. Incrementó los ferrocarriles, y progresó en la economía. México había sufrido por mucho tiempo, la plaga económica. El pequeño grupo de ricos, fueron inmensamente más ricos y las masas pobres, como Isabel dice… «tenían algo que comer».

Muchos campesinos no estaban satisfechos con las migajas y surgió la revuelta agraria que terminó con las fuerzas de Díaz, comenzando así la revolución de 1910. Cuando él supo que no tenía alternativa de ganar, se marchó a Europa, llevándose sus tesoros. Murió en París en 1915.

La vida en la hacienda

Isabel continúa diciéndome que:

«En Potreros de los Ocotes, conocido por el rancho de los pobres, cada uno tenía su pequeña casa propia. Esto estaba localizado en el área de la hacienda del General Juan Pérez Castro, Hacienda de Castro, como así la llamábamos, el general de los ricos. Él quería comprar todo y quería comprarlo muy barato. Echó una presa y no dejó a los pobres que agarraran agua, ni leña, ni na de na. Después los pobres trataron de venderle sus tierras pero él no quiso comprarlas. Él era el dueño del agua, de todas las tierras, porque era dueño de todo. Y le digo, que este general está ahora quemándose en los infiernos.»

- Cuénteme Isabel… ¿Cómo era la hacienda?

- Era muy grande, había muchos trabajadores, allí había, mire, había muchos ganados de reses, borregos, había chivos, había bueyes, había vacas muy grandes, ganados, eran puros ganados, oiga, de caballos y de todo había en la hacienda. Vivía mucha gente. Más o menos que había veces que fíjese, la estadía era muy grande, se sembraban puros chilares, chile de diferente ancho, delgao, chico y de todo ¡Eh! de todo.»

Cuando Isabel con un gesto muy gracioso dice ¡Eh!, se queda pensando, como si estuviera viendo los chilares y evoca tantas memorias y tantas otras experiencias que transcribo:

«Pero lo iban sembrando así, na más y al tiempo que pasaban unos días y hacían pajeras y allí lo echaban después y se secaba muy bien el chile y luego pa vendelo, no sé a qué precio lo vendían. Yo no trabajaba. Yo miraba, veía lo que hacían, porque por entonces yo era una niña. Sí. Era muy niña…» – Comenta riéndose-. «Yo jugaba con mis hermanos, que fuimos creciendo allí en el rancho. No había nada en qué jugar ni teníamos juguetes, hacíamos caballitos y corríamos en esos caballitos que hacíamos con palos, íbamos corriendo como los tontos. Me gustaba jugar con mis hermanos, más que con las muñecas, porque no había muñecas y estábamos casi iguales mi hermano y yo. Él tenía dos años más que yo. Jugábamos mucho… Y cuando yo estaba chica, no había retratos. No conocía yo los retratos, oiga, porque aquello era un monte y era muy grande y yo aprendí a hacer lo que hacía mi madre.»

- ¿Y qué hacía su madre?

- Pues moler. ¡Echar tortillas! Yo molía mis tamales. Metate. No conocíamos los molinos y molía con metate, así, mire…»

Chavelita hace los gestos con sus manos y luego da palmas graciosamente imitando como lo hacía entonces.

-¿Qué es un metate, Isabel?

- Son bases grandes, hacinas y luego tienen una pata grande atrás y dos chiquitas adelante y allí están entonces, echa uno el tamal y ya uno lo muele y lo quebra y luego lo muele y luego ya hace la masa remolida y luego la tortean.

Isabel sigue dando palmas como si lo estuviese haciendo y sigue comentando:

«Y ya echan las tortillas en comales de barro, de hierro. Luego lo ponían en la lumbre, no había chimenea, no había nada. Nuestras casas eran de adobe, muy pobres, goteaban y todo cuando llovía mucho y pasaba una trabajo con ello. La gente batallaba mucho, mi hermano no. Porque mi hermano supo leer. Él iba de un lugar a otro; mi mamá sí sabía leer también. Pero yo no hacía apenas nada cuando era niña. Mi hermana grande hacía toallas, eso lo hacía yo también mucho después. En aquellos tiempos se hacían toallas con deshilaos, porque en La Encarnación, las hacían pa los ranchos, por docenas. Y la gente pobre de los ranchos ganaban bastante, había varias clases de toallas, eran dobles y tenían un deshilao así, y otro así y contaban tres y salía una flor grande. Las chiquitas na más un desilao pa un lao y otro pa otro lao. Las que eran prontas, no tardaban en hacerlas, las otras tardaban más. Y a veces tardaban mucho tiempo en hacerlas. Se juntaban una a un lao y otra a otro y se acompañaban dos y tres haciéndolas.

-¿Se acuerda de alguna canción de entonces, Isabel?

- Sí. Sabía muchas canciones. Y ahora que las oigo en la radio las recuerdo, aunque las cambian al cantarlas. Recuerdo pedacitos así…

(Señala graciosamente esos pedacitos que recuerda)

Y yo le cantaba a mi mamá así…

Le dirás a tu mamá

que no te ande regañando,

porque nos hemos de ir

y te has de quedar llorando.

Esta canción, le gustaba mucho a mi mamá, mucho. Y yo se la cantaba muchas veces, me gustaba cantala. Y ahora me acuerdo de una, la del abandonao, oiga, esa de…

Me abandonaste mujer

porque soy muy pobre,

y la desgracia que ya sea casao

¿Pero qué he de hacer

si soy el abandonao?

Esto son na más pedacitos. Y le voy a contar. Que cuando yo tenía mis dientes, me gustaba mucho chiflar, chiflaba canciones. Ahora no puedo porque los dientes papan y los de uno no. Yo chiflaba mucho cuando era niña y después también, me ha gustado mucho chiflar. Pero lo que más me gustó de chica era barrer. Más que nada, oiga. Cuando estábamos en secciones y estábamos en lugares amplios, en patios grandes, yo barría mucho, con luna y todo en la noche. Y cuando barro siento pues…

jale y jale y jale, y ejercicios, mucho ejercicio. Cuando sale la dieta no la dejan a una barrer, dicen que hace mal, pero a mi me gusta mucho barrer. Cuando era niña , yo quería bailar, me gustaba bailar, pero mi papá no me dejaba, me daban ganas de bailar siempre. Yo decía que no, aunque sí quería. ¿Y sabe lo que también me gustaba mucho? Pues los columpios me encantaban. Eran unos columpios grandes los que teníamos y jiiiiiiiip!»

Isabel se ríe mucho, disfruta recordando su infancia, como si volviera a sentir aquellos momentos. La dejo que hable y recuerde sus juegos…

«Le digo que a los árboles no subía, pero a los columpios sí, nos columpiábamos mucho. Aunque siempre prefiero barrer. Cuando barría, chiflaba recio, y bailaba con la escoba y me divertía mucho y tenía pajaritos. Tenía gorriones, muchos pájaros, los que más me gustaban eran los sinsoles, son chiquitos pero muy cantadores y cuestan dinero. Son como los pájaros prietos, son parditos. Y los gorriones me encantaban también. Los machos tienen el buche colorado y las hembras no. Todos son muy cantadores. Allí era monte y el chonce, que todo aprende, si usted canta algunas canciones, él las aprende también, como las cotorras y los pericos. Son muy chismosos estos pájaros. ¿Y sabe? Cuando yo cantaba, ellos cantaban también. Me gustaban mucho. Pero ya después no pude velos más.»

Chavelita es muy expresiva, vive cada instante de sus recuerdos y sabe comunicármelos con sus gestos.

«Más tarde, cuando mi padre se hizo un poco grandes, se fue de ese rancho que le digo, ya no trabajó más allí, porque se dio un golpe, y ya no pudo trabajar. Él tenía un brazo tieso, porque se lo lastimó de aquí. (Señala con su mano el codo) Se lo rompió este hueso de aquí y ya después con este huesito así pues araba la tierra como podía. Pero en el traque ya no trabajó. ¿Sabe lo que hacía mi papá? Pues magüeyes. Que había muchos magüeyes, de esos grandotes que dan agua y miel. Son unos magüelles grandes, están para este lao también. Y quebraba y sacaba agua y miel, y hacía pulque. Eso hacía mi papá, pa tomá, pulque. Es como un agua fresca que emborracha, sí, emborracha. No tiene alcohol pero lo mesmo fuerte del agua miel y el pulque se va haciendo y hierve y eso toman y se emborrachan. Lo hierven y nada más. Lo echan el agua miel y agarra fuerza y se emborrachan. Mi papá se emborrachaba y los señores que lo hacían pues también se emborrachaban. No me gustó a mí, nunca lo tomé. «

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

Vida familiar

Chavelita estaba sentada en una silla frente a su altar, retomamos la conversación y me siguió platicando…

«Pues mire, yo le doy gracias a Dios. Que vale más que lo tengan a uno así, que lo dejen libre, porque mi papá era muy duro. Él no quería que yo tuviera unas amigas. Sólo me dejaba jugar con mis hermanas y na más. Pero sí tenía una amiga buena. Y él me decía que no, «que no traigas amigas» Y decía yo que no eran malas amigas, que eran muy buenas. Y yo decía para mis adentros que yo no las voy a correr. Que me da vergüenza, de modo que cuando iban estas muchachas buenas mi papá no las dejaba y que no quería. Y me dicía: ´vale más que no te andes juntando con fulana´. Y así nos iba retirando, mi papá no me ayudaba en mi casa, oiga.»

Isabel se pone triste recordando a sus amigas y continúa hablando.

«Fuimos ocho, entre hermanos y hermanas, pero cuatro murieron. Solamente un hombre y tres mujeres quedamos vivos. Sí. Hemos sido ocho. Yo tuve dos hermanas, una mayor que yo y la otra más joven. Mi hermana mayor se casó y vivió lejos. Mi hermana más joven, Lucía, las dos hacíamos todo el trabajo juntas. Ella era muy buena, siempre hacía lo que yo le pedía. Me decía ´vamos a cantar´, y dicía yo, y si, las dos cantábamos. Ella se casó antes que yo. Después, ya no volvimos a vernos. Cuando yo dejé México, ella ya tenía muchos niños. Uno de ellos murió. Pero no recuerdo las canciones que cantábamos mi hermana y yo. Recuerdo otras cosas pero no las canciones , esas no las recuerdo. Mi hermana mayor se llamaba Justina, con ella me peleaba más. Ella no me quería a mi porque yo era muy floja y no quería moler, y ella lo hacía y yo no. Y mi mamá me ayudaba a mí. Y dicía mi mamá: ´déjala que tortee, que vaya a juntar tunas´. Las tunas son las frutas del nopal. Y ella mi hermana Justina, se enfadaba mucho conmigo. Pero yo echaba cal a las tortillas y salían nejas (feas) y las de ella salían blancas. Y ella preguntaba: ´¿Qué ocurre aquí?´pero yo no decía nada.

Chavelita sonríe de una forma pícara. Se levanta de su silla y se da un paseo por su salón. Se vuelve a sentar y continúa diciéndome:

«Le diré que mi papá maltrataba a mi mamá y yo me enojaba mucho por eso. Y por ese motivo yo duré más tiempo sin casarme. Recuerdo cuando era jovencita que no quería dejar a mi mamá sola. Mi mamá era una mujer muy buena. Y al final mi papá quedó solo y pagó por lo que hizo, porque él no era bueno para mi mamá. Y cuando mi papá se quedó viudo, se murió de una cruda que tuvo, sí, mire usted, de eso murió. Porque al quedarse solo, necesitaba a mi madre, porque mi madre lo cuidaba con medecinas, porque él se ponía muy malo de las crudas y de eso murió porque ya nadie lo curó.»

Isabel se pone triste, sufre recordando estas escenas.

«Le diré que yo no tenía muchas cosas, pero tenía un gato que me acompañaba, era pintito, muy bueno, me gustaban los gatos y también los perros. Pero mi gato era muy amigo mío y muy bueno. Y con él me acompañaba cuando era niña. «

Este recuerdo la consuela. Y me sigue comentando acerca de su familia.

«Mi padre, nunca me dejó trabajar, yo miraba a las muchachas que estaban trabajando y andaban muy bien vestidas, yo quería trabajar en las casas grandes, en las casas de los ricos, pero el dicía que no y que no. Porque se aprovechaban de las criadas. Y era cierto que se aprovechaban de ellas por aquellos días. El me dijo: ´¿Sabes lo que vas a hacer? Pues vas a trabajar aquí en casa.´Y eso hice. Molía y molía y ganaba un centavo y hasta tres. Y me dijo mi papá que mejor criar marranos y criar gallinas y criar animales y hasta me dijo que me iba a comprar una máquina para coser. Y me la compró, y aprendí a coser y también a criar animales. Yo luego me enseñé a coser y hacía naguas y chomites de lana, colorados, azules, de muchos colores. Y a los colorados los ponía un corte y parecían como la bandera de México. Y los chomites se vendían por yardas y se ponían, y todo eso se acabó ya. Y me decía mi papá: ´Aprétame diez centavos´ y yo decía que no, pa tomar, y después se emborrachaba y no, yo no le quería dar dinero para la bebida. Pero ya le dije que a mi papá le gustaba mucho beber. Tuvo otra mujer y le metió ella en la bebida. Cuando se emborrachaba le daba a ella lástima, pero era ella muy rezandera, porque sabía leer y le rezaba al Santo Niño y a todos los santos. Pero mi papé bebía y bebía.»

Chavelita me mira recordando aquellos tiempos de su familia. Y hace un descanso y se arropa con el rebozo y sigue hablando.

Le diré que cuando era niña no sólo me gustaba barrer, me gustaba mucho bailar ya le he dicho que bailaba con mi escoba, pero mi papá era muy delicado, y no quería que yo bailara nada. ¿Y sabe lo que le digo? Que antes mandaban los mayores, los papás. Ahora ya no. Ellos dicen ya tengo la edad… ¡Y ya tengo la edad! ¿Y a los cuántos años tienen la edad? Pues son demasiado jóvenes. Y yo tenía veintidós años y todavía estaba allí en casa y no me dejaban salir.»

Isabel mezcla cosas, deseos, recuerdos, emociones vividas en sus primeros años, su infancia, su adolescencia, el recuerdo de sus padres es muy fuerte todavía en ella.

«Cuando yo tenía unos ocho años, iba a un lugar llamado León de las Aldamas. Mis hermanos pequeños iban conmigo y ellos pedían agua, y yo iba a los lugares de negocios a ver si nos daban algo de comer. A mi me gustaba mucho ir a los lugares a mirar qué había y también me gustaba divertir a los chavalitos. Cuando era niña, no llevaba zapatos. Luego sí. Porque luego criaba gallinas, pero cuando no trabajaba no tenía zapatos. Cuando trabaja sí tenía. Cuando yo era niña, mi papá era pobre, muy pobre. A veces íbamos a Misa a San Matías, y mi madrina me decía: Vamos a Misa´ y yo no podía ir, le decía que no, porque yo no tenía zapatos, y ella me decía: ´Ven conmigo que Don Exiquio tiene zapatos´. Y luego yo le decía, no tengo naguas, y ella me dio naguas y por fin fuimos a Misa.

La sonrisa de Isabel, es tan amplia y tan hermosa como su altarcito, se alegra con los bellos recuerdos y casi llora con los tristes. Sonreímos y me sigue contando…

«El esposo de mi hermana Lucía, se llamaba Porfirio y le llamaban «El Presidente», se casó con mi hermana a los dieciséis años o diecisiete. Él era ya hombre más viejo y era pastor y tenía su mamá y él, pero era pastor de chivas y mi hermana era chaparrita y no era fea, era muy guapa. Allí pasamos temporadas y pasamos muchos trabajos, porque no teníamos comida. Poníamos trampas para los pajaritos y el pajarito caía en el maíz, y así caían los pájaros y ese el alimento que teníamos, porque ese año no teníamos nada. En Potrero de los Ocotes, fue donde se quedó mi hermana. Había un corral de piedra alrededor del lugar. Ahí fue donde iba un hombre a matar a mi papá. Le tiró, fíjese, le tiró un tiro, pero la bala se clavó en la puerta. Mi papá lo persiguió con su navaja y cuando volvió a casa estaba ensangrentado. Nos asustamos mucho. Pero no era nada. Mi papá le había cortado un dedo al que lo perseguía pa quitale la pistola. El hombre que era rico, se huyó en su caballo. Estaría loco.»

Isabel me cuenta esta hazaña de su papá, como una verdadera locura.

y sigue recordando más lugares.

«Cerca de Aguas Calientes, estaba El Tigre. Y El Tigre, estaba junto a

La Encarnación, más cerca que de Aguas Calientes. Allí trabajaba mi papá en el traque. Que el traque es el tren. Y también trabajó en un lugar que se llama Peñuelas. Trabajaba de velador, era muy traquero mi papá. Velaba en la noche porque entonces, había muchos trampas encima de los trenes, y yo creo que iban también americanos… Yo conocí a los americanos en México. Eran muy grandotes, pasaban a pie, por eso los decían trampas, porque se pasaban al tren y porque eran muy grandotes y cómo mataban marranos, oiga que llevaban unos cueros de marranos y los tendían allí en el suelo y dormían sobre ellos. Iban a mirar, a ver, pues cada año llegaban muchos trenes especiales.

Ellos disfrutaban viendo las ciudades bonitas mucho antes de que viniera la revolución, ahora están muy desastradas esas ciudades, unas partes las echaron a balazos, y después no las reconstruyeron.

«En la Encarnación, había muchos guardias que cuidaban si los rieles del tren estaban quebrados. Mi papá era un guardia y al tiempo de ir a mirar, vio a un señor y contó mi papá: ´agarren un tarrito, que ese hombre tiene las piernas mochas´ y así fue. Lo pusimos en un lugar que no había piedras y con un jarrito le dimos agua, y mi mamá que sabía leer, llevó el libro de oraciones. El hombre se quejaba y le dimos agua y le preguntamos que como se llamaba y nos dijo que se llamaba Celto, y que era de Guanajuato. Y mi mamá estaba muy preocupada y puso el libro entre sus manos y leyó oraciones, y ella me dijo que me asomara a ver si yo veía venir gente y mi mamá, leyó mucho. Yo Vi que venía un señor con un caballo a pie, pa no pasar la cerca. Y yo les indiqué que venía ese señor y me fui. Pero mi mamá se quedó y ese señor era un sacerdote, un padrecito que confesó a ese hombre. El sacerdote dijo que no lo dejáramos solo porque iba a morir. Y después llegó el comisario y el hombre murió. El hombre que estaba tendido en el suelo quedó muerto allí mismo. Y se lo llevaron. Porque en los caminos maltrataban y morían así como le estoy contando.»

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

El noviazgo con Marcelino Amezquita

Isabel, conoció a su esposo en la Hacienda de Castro.

«Lo conocí porque allí vivíamos, porque mire, ya después que nosotros nos cambiamos adonde le digo que hacía pulque mi papá, como a él le gustaba el pulque, íbamos para allá, era un ranchito que estaba allí y la hacienda se llamaba así, Santa María.»

Chavelita sonríe, recuerda con nostalgia aquel lugar.

«Mi papá hacía y vendía pulque en unos jarritos así, dos centavos y tres centavos, según fueran los jarritos. La gente compraba y se emborrachaban todos mucho, porque había veces que hacía mi papá tres o cuatro ollas grandes y lo vendía todo. Estábamos en este rancho, como le digo, y duramos como dos años de novios. Pero en ese rancho que era Los Soportes, entonces yo venía a Misa a la Hacienda de Castro y allí me lo encontré. Yo no sabía de nada, oiga, de nada, muy tontuna era yo ¡eh!. Yo no estaba enterada, no, no, pues es lo que le digo yo, que no sabía como había que ser novia. Ahora los besos se usan mucho y entonces no se usaban nada, a mi nunca me besó.»

Isabel se ríe y sigue contándome.

«Antes, se decían por señas, yo creo que ni las comprendía yo las señas. Pero con una seña que me hizo yo creo que si lo entendí. Él sí me platicaba, pero yo na más le oía lo que decía, pues no sabía corresponder a nada. Una vez, recuerdo que me dijo que si yo miraba bien a su madre, él estaría contento y yo le dije que si ella se portaba bien conmigo, yo estaría contenta. Y eso es lo que nos hizo hacernos novios. Pero yo no lo miraba a la cara, me daba vergüenza. En México había unos rebozos grandes y yo me cobijaba de atrás del pescuezo y así lo escuchaba y empezó a platicarme y me abrazó.»

Chavelita me mira con ojos picarones y sonríe y después continúa hablando…

«Allá, los padres decían que había veces que los hombres que no lo diera una facultad para que lo agarraran y lo hicieran para allá y lo hicieran para acá. Pero ni cuando nos casamos yo creo que me besó. No hubo besos para mi, pero él fue muy bueno conmigo y tuvimos diez hijos, cinco hombres y cinco mujeres. Pero eso sí, no me acuerdo que me besara. Platicábamos un poquito y me quería, y yo me dejaba querer, pero él era muy serio y no se andaba jugando.»

En el acta que leí al principio dice:

«Al margen. Sta. María-Exiquia se casó con Marcelino Amezquita el día 17 de abril de 1915. La partida se encuentra en el libro número 21. Folio 90. Sr. Pérez»

Isabel no tenía todavía los 24 años de edad cuando se casó.

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

CAPÍTULO 2

REVOLUCIÓN Y TIEMPOS DIFÍCILES

Isabel recuerda su boda, sus amores y retorna a su juventud, pero especialmente a la revolución, ella tomó parte en aquellos acontecimientos.

Madero

«Cuando entró Madero, Noviembre 6, 1911, yo tenía más o menos, unos veinte años, pero Madero no se recibió de presidente porque lo mataron. Muchos estaban en contra de él, ahora no recuerdo, pero tenía muchos enemigos. Creo que él era bueno, pero lo mataron.»

Isabel ha quedado pensando largo rato, como si al decir «lo mataron» viera la sangre o recordara aquel momento trágico de México. Fechas inolvidables de 1911 a1913. La sublevación militar derribó al gobierno y el presidente Madero con el vicepresidente Pino Suárez, fueron asesinados.

Francisco Madero, nació en 1873 en San Pedro, en el Estado de Coahuila. Fue líder revolucionario y presidente, estudió en la Universidad de California y pasó seis años en Francia. A partir de 1900, se hizo popular en la política. Él organizó el club democrático Benito Juárez, con sucursales en todo el país. En la campaña de 1905, expresó sus ideas en contra del gobierno de Díaz. Él fue el líder conocido por establecer el voto independiente de los mexicanos. En 1908, publicó la Sucesión Presidencial de 1910, un claro y razonado informe de los problemas de México y una crítica sobre los métodos reglamentarios del gobierno de Díaz. El libro fue suspendido inmediatamente pero esto le dio a Madero una fama política en contra de Díaz, que le pondría a la cabeza a la hora de competir con Díaz en las elecciones. Madero fue encarcelado por hablar en contra del gobierno. Más tarde, cruzó el borde y desde San Antonio, Texas, el 5 de Octubre de 1910, llamó a la revolución y anunció el plan de San Luis de Potosí, que era una definitiva plataforma política. En Chihuahua, se juntó a las armas rebeldes y otros estados se juntaron a ellos. Así, meses más tarde, Madero fue elegido por una mayoría muy numerosa de votos, como presidente de México. En Noviembre 6, 1911, su gobierno fue inaugurado. Madero hizo un sincero esfuerzo para gobernar de acuerdo con la Constitución. Sus ideales consistían en dividir la tierra. Conoció varias dificultades porque retuvo el viejo congreso de Díaz. Mientras tanto Zapata, Orozco y Feliz Díaz, se revelaban en el Norte y en el Sur y fue el general Huerta con su armada el que consiguió la salida de Madero. En Febrero 22, en la prisión, Madero conoció la muerte. Los guardias de Huerta lo mataron en 1913.

«Yo tenía 19 ó 20 años cuando todo este lío de Madero, no le dieron tiempo para hacer nada, oiga, nada. No sabemos cómo sería, pero que él era bueno, eso es lo que a mi me parecía.»

Las guerras de la muerte

Después de un grande silencio, Isabel pregunta: «¿Usted sabe algo acerca de la guerra de México?»

- «No, Isabel. Yo apenas sé nada de México. En España se habla muy poco de estas guerras de México»

«Pues fíjese que entre todos, había 16 generales, eso oía yo. Y le diré que después de la hacienda, pues nos venimos después, cuando se puso la guerra se salió mucha gente. Y cuando entró este, entró también Villa, y luego que mataron a Madero, pues vinieron los carrancistas y luego sepa Dios! ¡Tanto general! ¡Eh! ¿Y quién fue el que ganó? Pues le digo que fue Carranza. Porque Villa lo lo lo… ¿Cómo le dijera? Perdió. Porque lo sitiaron. Por eso perdió, si no lo hubieran sitiao, pero cuando supo ya no, ya estaba en un rincón, sitiao.»

Isabel se levanta a mirar sus frijoles, los mueve con una cuchara, los prueba, deja la cuchara en un lado de la mesa y vuelve a contarme su historia.

«Los Carrancistas nunca fueron buenos, eran malos. Los Villistas eran buenos, por eso yo considero a los de allá. Yo me acuerdo que cuando era chiquita, decían mis abuelitos que hacía mucha guerra allá porque pasaban las tropas a pie, se usaban las pistolas, los rifles y los sables, y eso era lo que llevaban, cuando pasaban por los caminos, brillaban los sables grandotes, que yo los vi, así de grandotes, (extendiendo sus brazos expresa Isabel cómo eran de grandes). Muchas gentes a pie, era como una cuerda larga, porque a pie, oiga, a pie, pasaban mucho los soldados hasta acá, decían que el que iba muy cansao, pues decían que dieran tres pasos al frente y uno atrás. Y el que caía, lo mataban y lo dejaban allí pelao. A nosotros no nos dejaban verlo porque éramos chicos, pero la gente y mis abuelitos lo veían todo.

«Después, naide quería hacer eso porque tenían miedo. Caminaban a pie porque no había tren, ni carros, no había nada, y ya le digo, ellos sí los miraban, estaban guerreando, y decían: «¡Están guerreando, están guerreando!». Y al otro lao se oía. Y en México, esa guerra que hubo que eran mexicanos con mexicanos, no tenían otra nación de por medio, y con esos guerrearon y no con otros. ¡Y ahora, sabrá Dios lo que pasa allí! Todos los presidentes, como dice el dicho: «El que tiene querer más poder.» Y sabrá Dios… Y yo digo, pues de una patada me muero. Ustedes que están todavía lo verán.

«Yo recuerdo eso. Hasta que la guerra vino, todos los presidentes eran buenos. Pero después, después todos fueron malos.»

Isabel sonríe, sigue hablando de las guerras y de sus inmensas tristezas.

«!Las guerras de la muerte!» -comenta-. «Mi esposo sólo era un trabajador. Él no se metía en política. Trabajaba en esos caminos de hierro. Cuando veníamos de allá, él trabajaba y tuve diez hijos con él. Sí, con mi marido y sólo con él. Siete murieron, quedaron tres, dos hijas y un hijo, y con esos tengo muchos biznietos y tataranietos. Me ha cundido mucho mi familia, le digo y na más que, ¡esta familia es mía! Porque mi esposo me dejó estos tres hijos, y eso me ha cundido mucho, mucho, sí, y he sufrido bastante. Porque mire, en 1915, salimos de Santa María.

«Me fui con mi esposo y su familia, su madre, sus hermanos. Toda mi familia quedó atrás, así que no tenía familia, no tenía a nadie. Me fui sola. Y no he vuelto a ver a nadie de mi familia después.

«Yo tenía dos años de casada, y estuvimos varios años, hasta el 19, levantando los caminos de hierro, porque los trenes venían zumbando y lo venían levantando nuestros hombres, y caminaba más y así en medio de los peligros veníamos y Dios nos ayudó, duramos cuatro años de un lao pa otro lao, estuvimos en México y no teníamos casa y andábamos por muchos lugares huyendo de los Carrancistas, porque después de Madero, ya le he dicho que entró Carranza.»

Isabel se pierde de nuevo, recordando los caminos recorridos, sus palabras se mezclan, sonríe, prefiere reír al dolor que le tiembla en sus labios, haciendo así del recuerdo, algo más fuerte que el llanto y la tristeza que le supone recordarlo.

Foto de Pancho Villa, mostrada por Isabel Amezquita

Carranza y Villa: Estudio en Blanco y Negro

Isabel, junta sus manos como si fuera a decir una oración, como si fuera a hacer una súplica. Por fin, estallan sus palabras. Su voz se transforma, se hace más fuerte y más enérgica.

«¡Villa era bueno y Carranza era malo! ¡Villa defendía a los pobres! Y nosotros éramos pobres. Y Carranza defendía a los ricos. Y nosotros no éramos ricos. Villa aborrecía a los ricos porque los ricos no querían a los pobres nada, lo que se dice nada. A veces iba un pobre a pedir trabajo aun rico y estos ricos los echaban a patadas con el sobrero quitao, que yo lo he visto, no eran buenos los ricos entonces, ni Carranza tampoco era bueno. Y las haciendas eran de ellos, de los ricos.

«Cuando la revolución también hicieron muchas cosas malas, tumbaron muchas casas, derrumbaron calles enteras. Y cuando fui con Lupe, todo estaba destruido. Y de Carranza no hablan, y ese fue más malo que ningún otro. A Villa que era bueno, no hablan nada. Carranza era un verdadero diablo, oiga. Nos hacían esconder las tortillas y golpeaban a las mujeres porque no daban de comer. Hacían cenizas con la carne, pues la quemaban y nos traíban, y decían: ´»Ya comieron los muchachitos» Y no era verdad. Los Carrancistas sacaban los santos de las iglesias y los corrían con caballos. Y se burlaban de las hostias, y echaban a los caballos a las iglesias a destruir y pisotear todo lo que había. Y en Mapimi, quisieron sacar al Señor Bendito y no pudieron porque era vivo y se engarruñó, se quedó parao el que lo iba a sacar. Y con los padrecitos hacían grandes herejías. Los padres iban a confesar a escondidas y los mataban a esos pobres clérigos.»

Isabel pasó hambre, dolor y miedo en esta revolución, en esta huída de guerra, en este camino horrible de muerte y miseria. Después de un rato, me pregunta si yo no he conocido a Villa o a Carranza. Le digo que no, pero prometo enterarme de quien fue el malo de Carranza.

Venustiano Carranza nació en 1859 en Cuatro Ciénagas, Coahuila. Se educó en la ciudad de México y regresó después al Estado de Coahuila adonde fue Senador desde 1901 hasta 1911. En 1910, unió la revolución de Francisco Madero contra el presidente Porfirio Díaz. Cuando ganó Madero, Carranza fue elegido gobernador de Coahuila, y cuando Madero fue asesinado, él continuaba en este puesto, desde donde protestó contra el crimen cometido. Después, Carranza vino a ser el líder de la revolución contra el General Victoriano Huerta, y fue reconocido por los revolucionarios con el sobrenombre de «primer jefe».

Carranza inició la importante reforma social y económica. La nacionalización del petróleo y el carbón, promocionó los dones comunes de los ejidos y protegió la ley de labor del campo. Estas reformas fueron más tarde incluidas en la Constitución de 1917.

Después, cuando el General Huerta fue forzado a dejar el país, Villa y otros líderes militares se tornaron contra Carranza.

A pesar de estos problemas que surgieron, Carranza promulgó la nueva Constitución de México, el 5 de Febrero de 1917, y en Mayo 1, del mismo año, fue elegido presidente. El quería reconstruir su país cuando los Estados Unidos entraron en la guerra mundial. México quedó neutral por decisión de Carranza que quiso guardar su país fuera de la influencia de Estados Unidos. Se esforzó por cooperar con los países de América Latina.

En 1920, en las elecciones presidenciales, dos candidatos líderes, Álvaro Obregón y Pablo González, se revolvieron en contra suya y del gobierno militar, entonces Carranza dejó la ciudad de México ante inseguridad. Se fue a Veracruz con el fin de organizar allí a sus seguidores. Pero en Tlaxcalaltongo, Puebla, fue asesinado por fuerzas de Obregón en Mayo 21, del año de 1920.

En esta época, Isabel ya no estaría en México.

-¿Qué recuerda usted de Villa, Isabel?

«Yo conocí a Villa en persona, era muy bueno, tenía bigotes, y era muy respetuoso, te miraba muy respetuoso, no era muy chaparro, ni tampoco era muy alto, era gruesecito. Pero mire, aquí lo tengo… Nosotros íbamos con Villa.

Isabel me enseña un viejo retrato de Villa y algunas fotos…

«Yo creo que ya era viejo, no estaba casao, dicen que tenía mujeres aquí y mujeres allá. Y hasta decían que una vez lo iban a matar a traición las mujeres porque las engañaba y ellas estaban enojadas con él.»

Isabel vuelve a la cocina, camina derecha, graciosa en sus movimientos, pone agua a los frijoles, los vuelve a probar. «Están ricos», comenta chupando la cuchara.

«A Pancho Villa lo conocimos al salir de allá, lo conocí cuando ya venía él de correr, y yo lo conocí allí en la Hacienda de Castro. Él pasaba con su gente que le seguía y con él nos vinimos todos nosotros.

«Porque si, porque Villa era muy bueno con la gente. Y ¿sabía usted que cruzó la frontera con 400 hombres y entró a los Estados Unidos, yo oí a las gentes. Él nos protegía mucho, nos defendía y robaba a los ricos para dárnoslo a nosotros los pobres.»

El día 9 de Marzo de 1916, Villa entró al pueblo que Isabel refiere. Este pueblo era Columbus, en Nuevo México. Allí entró y mató a 16 estadounidenses y quemó el pueblo. El Presidente Wilson ordenó capturar a Villa y a su banda. Pero para hacer eso tenían que entrar dentro de México. Carranza no dejó entrar a las fuerzas norteamericanas de Estados Unidos en México, para ello puso resistencia de armas en el borde. Al ver la decisión de Carranza, inesperada, las tropas de Estados Unidos se retiraron y Villa cesó en su amenaza internacional.

Pancho Villa fue un revolucionario de México. Nació el mismo día que Madero, 4 de Octubre, cuatro años antes que él, en 1877. Villa nació en Río Grande, en el Estado de Durango. Cuando era joven, no tenía casa, iba de un lado para otro y llegó a crear una banda, cambió su nombre real de Doroteo Arango, conocido en la región por sus crímenes y andadas. Él se unió a Madero en la revolución contra Díaz.

Villa fue capturado por Victoriano Huerta durante la campaña, pero él escapó a Texas.

En 1914, volvió a México y se unió a las fuerzas de Carranza, en contra de Huerta, que sacó a Madero y ganó la presidencia. Los dos generales ayudaron a Huerta, pero en el momento del triunfo, ellos no estaban de acuerdo en sus opiniones políticas. Carranza no quiso tratar con Villa, pensó que era un bandido y que no se fiaba de sus intenciones.

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

La retirada

«Nos vinimos en un tren y no na más nosotros, pues que vino mucha gente cuando perdió Villa, porque decían que Carranza era muy malo, así que nos vinimos con Pancho Villa porque él traía trenes, y cuántos caminos, oiga, aunque ya venía derrotado. Y luego nos vinimos con el General Contreras, por Cuencamé.

«Contreras era un buen Villista. Estuvimos con él cerca de seis meses. Este general tenía su casa y ahí nos vinimos, nos pusieron en un salón donde vivían mucha gente, y luego que estábamos allí, hacíamos cocina afuera. Teníamos poco de estar allí y ya decían que iban a caer los Carrancistas, y luego los Villistas que se iban a agarrar allí. Si le digo que salíamos, porque nosotros éramos Villistas. Muchas personas con las maletas cargadas, otras a pie, y todos andando, y cuántos caminos, y todos caíamos en un lugar que ni lo conocíamos. Y allí, sabe que allí tuvimos muy poco, porque no había trabajo y nosotros no teníamos dinero, éramos errantes, caminábamos… Porque le digo, que nosotros trabajábamos pero a veces, muchas veces, no nos daban trabajo y otras, era por comida, y así pasábamos el tiempo del camino.

«Cuando venían los Carrancistas, ellos tenían carne, se divertían allí en los cerros mataban bueyes y los robaban y se lo pasaban bien con la carne. Estábamos siempre en todo el peligro de esas guerras y cuando nos hallaban ya estábamos en una haciendo cerca del río Naza. Y en esa hacienda había mucha comida, pero mucha, allí si que comimos. Y ala gente le caímos muy bien, los hombres trabajaron, nosotros moliendo como traíbamos los metates, y allí pasamos una temporada, pero no teníamos casa. En ese lugar tuve una de mis niñas. Teníamos después un salón y ya le digo que allí nos miraron muy bien y había comida pero estaban los Carrancistas encima. Le digo que ellos mandaban ¡eh! mandaban mucho. De manera que llegamos y estábamos todos, hombres y mujeres revueltos, yo no sabía nada de la familia, y ya le he dicho, allí fue onde tuve mi primera niña, en una casa de caña, porque dijo mí suegra a los hombres que lo hicieran así que clavaran paredes, que hicieran la casa y había unas cañas grandotas, así, y después ellos hicieron dos cuartos y allí tuve la primera niña que se llamaba María Nicolasa, porque nació el día 2 de Febrero, el día de La Candelaria. Y como le digo, allí nació en la choza. Y me dijo mi suegra: «Van a caer los Carrancistas.» Y es que mi suegra estaba preocupada y me dijo más… «Pa que no pases el susto así na más te voy a bañar muy pronto porque va a ver pelea con los Villistas.» Y yo recién levantada. Pero ella me atendió muy bien. Mi suegra, ella nos miraba y cuidaba y andaba yo junto con otra concuña, porque eran dos hijos casados y un soltero y entonces hicieron esas casas de cañas entre todos los hijos y nos hicieron un cuarto y cortina y todo.

«Cuando entraron los Carrancistas, ya teníamos casas de caña ¡eh!, de pura caña!! Y el frío no entraba. Pero mi suegra me dijo: «Las balas si pueden entrar» Y me dijo que fuera a una casa con unos señores que había cerquita y cuando sucedía eso de la guerra pues iba corriendo con la niña y allí me escondía con la señora, así lo hice, corrí prontamente con mi niña y me escondí allí con ella y sepa Dios lo que herían, no sé.»

-¿Recuerda la fecha, Isabel?

«No. No sé. Cuando se acabó el tiroteo salí de allí, pero al mesmo tiempo oí que había escondido un soldado allí y las mujeres como eran muy mitoteras, salieron y le abrazaron. La señora donde yo me había escondido me preguntó si están allí los Villistas, pero ya le dije que no, si Nina más mataron y se fueron por el cerro.

«En Chihuahua, estuvimos bien a gusto porque había comida. A veces nos quedábamos en el monte porque no llevábamos nada, el tren de Villa nos dejó en Cuencamé, allí no había peligro, pero cuando llegaron a pelear tuvimos que salir, batallamos mucho hasta llegar a Chihuahua. Siempre teníamos detrás a los Carrancistas. Allí encontramos una casita alquilada. Villa nos protegía, él con la gente pacífica no peleaba, con los mortificados nunca peleaba Vila. Los Carrancistas arrasaron todo, se llevaron toda la comida, sin dejar nada a los pobres, los trigales estaban grandes y hermosos, y entraron los caballos de los Carrancistas y todo lo arrasaron, lo pisotearon, entraron los ganaos y toda la comida destrozada, llena de orines y suciedades y entonces dijo mi esposo: «Nos vamos a Torreón». Y nos fuimos. ¿Y sabe usted lo que comíamos? Pues cuando nos daba hambre, comíamos de ese sotol, de esos magasitos y los patinaba debajo y comíamos cuando nos daba hambre. Dicen que la gente que se quedó en ese rancho, se murió de hambre. Y si nosotros nos hubiésemos quedado allí, nos hubiésemos muerto también.

«yo iba en un tren de trabajadores, cuando íbamos a Torreón. A mí me pegó la viruela, y la niña mamaba y le pegó y nos corrieron del tren porque yo estaba virulenta, y todos nos fuimos, mi esposo y yo y mi suegra y el hijo Cesáreo y Refugio y mi cuñao y concuña y ella llevaba una niña y yo otra. Y a ella también se le murió la otra.

«Mi suegra me curaba cuando la viruela, me curaba con agua fresca porque mi niña quedó ciega, le salieron en los ojos y por eso yo le pedía a Dios que me la llevara. Y esa enfermedad quema y es una toda de color pinto y si se rasca deja huella y daba mucha comezón. Estuve dos meses y se quitaron hasta se secaron. Eran viruelas de las buenas. Hay locas que son peores, pero se secan pronto y las otras tienen como agua y a veces en los tayones pues se revientan.

«Así que llegamos a Torreón, yo ya llevaba a mi niña, estaban allí las casas solas, la gente había salido porque no tenían comida y no había nadie, y comíamos mesquites cocidos, porque no tenían comida y no había nadie, y comíamos eso, mesquites, porque en este tiempo llevábamos nosotros un burro y lo cargaban los hombres, iban al monte allá en Torreón, íbamos al pueblo, no tardamos mucho, nos llevaban en un cinco, íbamos y había comida en los parianes y en los mercados, pero ni una cascarita tirada, no, nadie nos daba nada. Puros mesquitos comíamos y eran cocidos.

«También había un vendedor allí, velando las casas, porque les hacían diabluras. Iba la gente allí y se metían en las casas y mi suegra se metió allí y allí nos metíbamos nosotros tras de ella. Mi suegra se hizo amiga del velador, Y le daba media libra de masa para que la torteara al señor que velaba y así nos agarraba una tortilla pa nosotros. Y a mi me daba un pedacito y decía que porque estábamos criando.»

Isabel recuerdo esta tortilla como algo muy especial, como un manjar delicioso, único, exquisito y todo esto ocurrí en Torreón.

Torreón era una villa muy importante. Allí tuvo lugar una de las más violentas batallas de la revolución, ocurrida en Marzo, entre el 20 de este mes y el día 2 de Abril de 1914. La ciudad estaba defendida por el General Refugio Velasco; sufrió un ataque salvaje, feroz, las tropas iban al mando de Pancho Villa, que a la vez iba reforzado por un grupo de generales y más de ocho mil hombres, 29 cañones, municiones, facilidades médicas, etc.. Y todo era transportado por tren. tomó la ciudad el 2 de Abril, Velasco se retiró. Esta batalla hizo victorioso a Villa y le dio fama de un gran soldado y de un gran héroe.

«Pues sí, mire usté, una tortilla ¡puros mesquites eh! Y estábamos criando. De modo que allí se acabó la comida y ya, ¿Para ande ganábamos? ¡Pa ende! Ya dijo mi esposo, que dieron una vuelta y hallaron un reenganche y nos fuimos a San Pedro de las Colonias, y hallaron un campo de trabajo. Y dejamos atrás la miseria y la batalla.

Allí se metieron a trabajar. No pagaban con dinero, pero sí con comida. Y los hombres día y noche trabajaban, levantaban los caminos de hierro, porque los Carrancista los tumbaban todos y andábamos en el peligro constante, en el mero peligro, oiga, pero no nos pasó nada, por eso le digo que Dios nos cuidó, sí, porque cuando nosotros salíamos de allá de México a correr caminos, dejé solos a mis padres.

» A veces no teníamos ni jabón pa lavarnos. Allí en Cuencamé, recuerdo que había jaboncillo y decían jaboncillo a aquello que sale de las peñas y eso era el jabón, porque pa bañarnos no teníamos. Pues le voy a decir a usted la pura verdad que hasta piojos teníamos. Mi cuñada tenía la cabeza sangrienta porque no teníamos jabón. Llegó un señor que vendía jabón y vendió a mi suegra un jabón y así nos bañamos en el río.

«Pero se nos acabó el dinero y quedamos otra vez muertos de hambre. Cuando finalmente conseguimos llegar a Chihuahua, allí estuvimos muy poco… pero un poco más confortables, pero tuvimos un tiempo muy difícil hasta conseguir Chihuahua.

«Muchas veces nos parábamos en los árboles. Y allí finalmente encontramos una casa pequeña donde vivir y con comida. Yo recuerdo que un tostón de oro era medio dólar, un pese na más, n oro valía dos pesos, con eso nos estábamos manteniendo, hasta que pudiéramos pasar a Estados Unidos. Pues siempre esperábamos papeles que no venían nunca, esperábamos luego en Juárez, cerca de El Paso, ya traía un niño que nació en Chihuahua. Eliodoro, y otro murió allí también, pero ese niño que nació allí, no tenía comida. Pues echamos pa otra parte y siempre con guerra. Y Villa siempre nos ayudaba. Pero Carranza nos perseguía siempre por donde íbamos.

«Recuerdo cuando salíamos de México y dejé a mis padres solos.»

Isabel rompe a llorar como si fuera una niña. Una niña que de repente se le hubiese roto su mejor juguete, llora con amor, con dolor, con recuerdos que hieren su alma dulcificando al mismo tiempo ese llanto sereno y frágil.

«Cuando salimos de allí, recuerdo que mi madre, mi padre, nos echaron la bendición, y sí, Dios nos ayudó mucho, mucho»

Sigue llorando, es un momento de silencio, recojo sus manos, mis palabras quieren ayudarla, sé que es inevitable esta emoción, la fuerte sensación de todo lo vivido.

- No llore Isabel. Yo estoy a su lado. Y a veces es bueno hablar de lo que hemos vivido tan intenso. Cuando me haya contado todo se va a sentir mejor.

«Sí, sí. Quedamos en las bendiciones de mi madre, que nos echó a los dos, a mi esposo y a mi y ya no la volvía ver nunca más, pero no más yo, mucha gente pasó por lo mismo, por eso yo considero a los que están allá, porque pienso cómo estarán todos. Las guerras donde guerrean, son muy tristes, muy tristes. Porque yo pasé por eso y considero las naciones que están unas en contra de otras, y esta nación donde ahora vivo, como digo yo, Estados Unidos, es muy bueno para mi, porque no hay guerra, yo no hablo de ningún presidente porque yo tengo aquí toda mi familia y me miran bien a todos y Estados Unidos se portó muy bien conmigo, gracias a Dios.»

Isabel sonríe ampliamente de nuevo, todo su rostro se ilumina de pronto, vuelve a la cocina, camina despacio, con la vista cansada pero con la energía todavía viva de su esperanza y de su felicidad que es su familia. ¡Cuánta miseria y dolor pasados! ¡Cuánta vida queda atrás para los que olvidan! Es como una herencia sin hijos, sin dueño, y todo va quedando en el camino para quien pueda y quiera apreciarlo.

Foto: Julie Sopetrán

CAPÍTULO 3

VIDA EN LA TIERRA SOÑADA

Dos años antes de que Villa muriera, Isabel con su esposo y un niño en los brazos vino a Estados Unidos.

«Nosotros entramos por el Río Grande, el río de Texas, un señor nos habló de venir a este país, porque en México no teníamos comida, no teníamos nada y mucha gente venía para Texas. Estuvimos antes como siete meses trabajando allí, donde le decía antes, donde trabajaban día y noche los hombres, algunos se desmayaban porque no comían y tantos unos como otros pasábamos muchos trabajos para vivir y luego acá la vida fue mejor. Pasamos el río a pata seca, caminando sin burro ni nada, sin ropa, sin cosas.»

Isabel mezcla alegrías y tristezas, parece recordar la huída a Egipto de María y José con el niño, pero sin burro, solos con la noche y el silencio, el miedo y el hambre.

«Un amigo nos salvó de to. Nos dijo que aquí estaríamos mejor, y nos ayudó a pasar el río, lo pasamos a pata, nosotros nos escondíamos, los hombres tenían miedo que pasara yo, que el niño comenzara a llorar en la noche y ellos se iban escondiendo y yo también, y una señora muy buena antes de salir me dio una costadita y mi niño no lloró, yo lo tenía a mi niño muy apretado contra mí y me escondí entre matorrales, y el río no traía agua porque era verano, mi niño no lloró y pasamos, pero mi niño murió en Texas. Ese niño que nació en Chihuahua, tenía mucha hambre, no estaba alimentado y murió en uno de aquellos lugares, murió de una diarrea na más pasar el río. Los otros que tuve antes, murieron en México y en los caminos.»

La emoción es inevitable en Isabel, la pérdida de sus hijos marca en ella un gesto de dolor.

«Pasamos sin ropa, lo dejamos todo en Juárez.

«Cuando cruzamos el río, ahora le voy a contar lo que pasó. Había un canal lleno de agua, y veíamos las luces en la distancia. Mi esposo se puso una sábana grandota para proteger al niño y na más. Los hombres llevaban corbatas puestas para que parecieran mejor y consiguieran trabajo enseguida. Había cuatro hombres. Cuando finalmente vimos la luz, caminamos hasta la casa. Allí había una mujer, su nombre era Pilar, y también había un hombre y tres niños. Ese señor nos ayudó mucho, pues éramos doce.

«La señora nos dio una taza de café; esta familia eran mexicanos que vivían en Texas, y nos dio café. Nos llevaron después a un rancho a unas casas que tenían las paredes caídas, el señor nos dejó en la noche y nos ayudó. Al día siguiente todo era distinto. ¡Y ándele que allí nos recuperamos! No encontrábamos camas, pues na más barríamos el suelo y allí nos quedábamos. La señora aquella me dio el cuerito de un borrego para acostar al niño, pero nosotros nos acostamos. ¿A que no sabe cómo? ¡Pues a chaqueta pelá en el suelo! otro día, la señora les dio de comer a los hombres y a todos nosotros. Y el señor buscó trabajo. Y ellos muy guapos se pusieron con corbatas y to. Y consiguieron trabajo pa hacer un garaje. Duraron cinco días allí y ya desde ese día teníamos comida. Todos los días nos traían alimentos y todos estábamos contentos porque le diré que todo estaba lleno.

«Mi concuña iba panzona y sin cama y sin na de ná. Pues había que comprá una colcha; todos se preocupaban y yo también. Pero necesitábamos una colcha pa cuando llegue el día, pensaba yo. Y duró dos meses más. Mi suegra fue la partera y yo le tenía y le ayudaba a mi suegra en esos quehaceres. Pero recuerdo que mi cuñada tuvo mal tiempo, comía tostadas y atole. No comía chili, no comía frijoles, porque le daba teta al niño, no tenía tetera. Pero pecho les dábamos a los hijos. Yo no tuve pecho para Lupe y sólo le di tetera. Se crían buenos y fuertes con pecho.

«Le dijeron a mi esposo que trabajara en ese mis rancho y allí duramos dos años. Ese rancho era de Ysleta, pero no recuerdo como se llamaba. Sé que estaba cerca del pueblo de Ysleta. Luego mi esposo trabajó en el Reclamex, era una oficina del gobierno y entramos a otra casa y vivíamos de renta.»

Alrededor de 1920, la familia de Isabel emigró a Nuevo México, siguiendo la cosecha del algodón.

«Cogíamos un tren hasta Carlsbad, allí fuimos a piscar algodón. Yo iba gorda de Lupe y ella nació en Carlsbad en 1920. Ella era mi cuarta. Recuerdo que iba a piscar con ella. Compramos bogue pa meter los bebés, y yo la llevaba en el bogue y allí estaba acostada y hasta que aprendió a correr.»

En Texas comenzaron una vida nueva. Encontraron trabajo, casa, amigos, y también un país nuevo y al mismo tiempo familiar ya que, en Texas todo era más fácil y allí había muchos mexicanos, refugiados de la revolución que buscaban paz y trabajo. Familias que ya ganaban un dinero y una libertad diferente a la experimentada en años anteriores; Los hijos de Isabel crecían como cualquier americano con raíces mexicanas; otra educación, otros problemas diferentes, otra cultura, sería la que diera cobijo a esta familia de Isabel.

Lupe, la hija mayor de Isabel, cuenta algunos detalles de la vida en Texas.

«Mi papá nos llevaba a la iglesia todos los domingos. Todavía conservo el libro de Misa de mi papá. También conservo su llavero. Mi papá tocaba la guitarra y mi mamá tenía muchos pájaros de diferente clases. Esto ocupaba el tiempo de mi mamá. Mi abuelita se enojaba porque mi mamá no trabajaba porque estaba con los pájaros. Ella en la noche los tapaba con mucho cuidado y los quería mucho.»

continúa Lupe, «Durante la Depresión, mi padre tenía un ranchito y le llamaban «Mister» en el pueblo de Ysleta. Él era muy limpio, decía: «una cosa es ser pobre y otra limpio». Hay que ser pobre pero limpio,y le gustaba vestir muy bien.»

Así comenzaron una vida nueva, pero lo más triste es que el esposo de Isabel se enfermó, y ni la medicina ni el curanderismo pudieron evitar esta tragedia.

Marcelino, su enfermedad y muerte

«A mi esposo le pusieron un mal, me lo embrujaron. Fue una señora la que hizo el mal. Él tenía un amigo, muy amigo, y lo llevó adonde esa señora. Porque ella estaba con mi cuñao, con el hermano de mi marido. Era la querida de mi cuñao, pa mejó decilo. Como tenía al hermano así, pues mi marido no la podía ver, no la quería. También dijeron que ella le había puesto un mal a mi cuñao. Y mi cuñao se murió. Mi esposo fue al camposanto a velo y allí estaba ella. Mi esposo fue a enterralo, y la vió a ella. Y ella le dijo que le abriera la caja. Y mi marido le dijo que no. Y de modo que también lo fregó, ¡bien fregao!.

Pues cuando él vino de allá, ya no supo si lo había llevao a enterrarlo o no, ya él nos preguntaba y dicía: ´¿Dónde está Cuco que no lo he visto?´. Se murió, decíamos nosotros. Y dicía cosas como que quién lo fue a enterrar y que se murió y todo se le olvidaba, lloraba mi esposo y ya ahí comenzó el mal porque lo había embrujao esta mujer y él se sentía muy mal. Un amigo fue el que lo llevó allí con ella para que lo quitara el mal y ella le dio un trago y lo volvió loco.

-«¿Sabe lo que le dio a beber, Isabel?»

-No. ¡Sepa Dios! Se lo dio en alcohol por eso andaba como borracho. Duró así cuatro años. Enfermo y siempre mal. «

Marcelino fue llevado a un médico.

«Yo no quería echarle al hospital, me lo decían que lo llevara, pero yo no quería. Pero lo llevé al hospital. Dije que aquí se tiene que morir, en su casa. Él tenía a su mamá conmigo. Teníamos una casita con dos cuartitos. De modo que ella estaba en su cuartito y yo en el mío. Yo iba a trabajar y ella se quedaba cuidando marido y le daba las medicinas.

«Finalmente el doctor, le dio de todo y no le hallaba más. Y no tenía remedio, porque no tenía pensamientos. Ya me dijo el doctor que ya le había dado de todo, oiga, de todo, y usted sabe que hay que hacer lo posible por la vida. Hay gente que dice que se le metió el diablo y muchas cosas más.»

- ¿Usted cree en eso, Isabel?

«Pues sabe que si, porque hay quien lo haga que me dan al diablo. El que hace mal… El diablo es como una persona que no la quiere a usted. Si la persona no lo sabe, paga a quien se lo haga, y luego usted no sabe ni lo que tiene. Le puede hacer el mal en cualquier cosa. En una comida, en la ropa, en todo. Y las hay porque a mí me decían, porque mire mi esposo duró cuatro años, pero dos años que no sabía nada, nada, le daba en la tina y na más. Comía una cosa y ya se levantaba. Pero después ya no. Por eso no nos conocía y eso es lo que me decía el doctor que no hallaba enfermedad alguna, que todo le había curado y no le hallaba y me decían que el curandero tal vez lo podría curar.

«Mi esposo murió joven. Creo que lleva muerto 40 años. «

Isabel está confundida en este dato, creyendo que él tenía 24 a 26 años. Actualmente, él era mayor y murió en 1937 a la edad de 47 años. Murió en Texas, y según Isabel, ella lleva en California 24 años.

Foto borrosa, Isabel tal vez con su suegra o algún familiar.

Notas de curanderismo y brujería

«Yo había oído hablar del curanderismo, de futano y del curandero mengano. Pues «tráigale» «tráigale» cuando me decían todo el tiempo. Y yo lo llevaba para que le curaran pero no le hacían nada. Un señor que era muy bueno, le dijo: «Mirra al tratar de sacarle el mal a su marido, el mal que es ella misma, no saldrá ella, saldrá el diablo en su lugar; demodé que el diablo no podemos hacer nada.» Y sabe que, varios curanderos mueren, los matan, cuando curan tienen el peligro que los maten. Es muy peligroso andar con esto. Y Nina más no la quieren a usted y le hacen un mal. Quiere hacer un bien y le hacen un mal, sea por envidia, por coraje, por lo que sea. Y esa señora era muy mala. Y el padre me decía que dicen en los sermones, me refiero a esos padres creyentes, pues dicen muchas cosas. Porque esa señora tanto mataba a los jóvenes como a las muchachas. Y hacían cosas a la fuerza. Si cuando una muchacha no quería a un muchacho, les pasaba un dolor y se morían. Y la conocí yo a esa mujer y la tenía miedo y a poco me hizo a mi también un daño.

«Y me decían los curanderos, allí en Texas, que le diera yo un golpe, pero que yo le tenía miedo ¿Cómo se lo daba? Yo andaba muy recio, y allá en este rancho, me caí, salía a las seis de la mañana porque estaba lejos y llegaba a pie en la tarde a la casa y en la mañana salía a las seis y en la tarde tenía que estar a las siete, porque era largo camino y llegaba a pie a la cama. Y andaba recio y me di una caída y me lastimé una pierna, hace como 27 años. Porque aquí vamos ya a 24 y en Texas estuve mucho.

«Mi muchacho estaba casao, ya le digo, y me di la caída y nunca se me quitaron los dolores y ahora con una señora de aquí me curó, anda aquí en Sunnyvale, es mexicana, pero ya tiene muchos años aquí y va mucha gente a verla. Y esa señora, ¿no sabe usted que me quitó el dolor? Y na más frío me daba y se engarrotaba y ya se estaba engarruñando la pata.»

-¿Cómo le curó, Isabel?

-«Pues soba y soba, masaje y le decía yo que me dolía la rodilla y me untó una medicina y ya estaba una rodilla más grande que la otra, y esa señora me ha quitao el dolor y ahora ando bien, por eso yo creo que me tocó alguna cosa porque mucha gente me envidia. Y yo como me he portado bien, me han envidiado, porque yo era seria y no hacía ruido. No platicaba, na más caminaba y caminaba, a veces hasta dormida me quedaba de tanto caminar…

Los trabajos y los días de Isabel

«Siempre estaba caminando, yendo y viniendo, en tanto calor. Y las tres de la mañana eran cuando me levantaba para dejar la comida a los muchachos para que fueran a la escuela. En el trabajo, me dormía na más. a veces les ofrecía lavales alguna cosa a los patrones pa ganar más y así poder mandar a mis muchachos a la escuela. Y me dormía, porque trabajaba mucho, pero usaba un sombrero grande, pues me tapaba los ojos. Cuando llegaba el patrón, él no sabía si yo estaba dormida y yo, que era muy lista, para enseguida abría los ojos, ya le digo, pues no se enteraba. Pero ese señor me quería a mi, porque consideraba, había veces que tenía hasta cien hombres y repartía el trabajo de cocinar a cuatro mujeres: 25 una, 25 otra. Y repartía 100 hombres, ándele, pues que estos hombres comían mucho. Y tenía algodón, y tenía flores y tenía melones, y tenía un rancho hermoso, este patrón mío. Él se llamaba Francisco Guarnal, en Texas. Pues ese señor, ¿sabe qué me decía? Pues me dicía: «Cuando tú tengas que hacer comida para mucha gente, no vengas a trabajar.» Él se refería a los hombres que iban a piscar. Algunos iban tarde, y los que van a trabajar todo el día, van temprano. Les daba de almorzar temprano, y los otros hasta que salían después, porque empezaban tarde, por el algodón que estaba mojao. Tenían que estar listos para el almuerzo. Había hombres que eran muy buenos y me ayudaban a freír los huevos, y mire, a veces me faltaban a mí tortillas y tenía que ir a la tienda y venir prontamente, y ellos iban en mi lugar. Tenía una señora que hacía las tortillas de harina. Pero yo tenía una estufa muy grande que era de leña. Seis quemadores tenía. Era muy grande. Esa estufa me ayudó mucho. La echaba yo cañetas, unas con dulces y otras con sal, pues me ayudaba mucho con eso. ¡Y tanto hombre, oiga! Y me pongo yo a pensar, cómo Dios me ayudaba, con tanto que hacer. Y sí, Dios me ayudaba, que se lo digo yo a usted que me ayudaba.

«Yo he trabajado noche y día, y hasta como dice el dicho, hasta ahora que me caí aquí. Con mis muchachos. Tenía que trabajar por estos nietos que mi hija tuvo. Tenía su casa, pero el papá no les hizo mucho aprecio porque se fue de soldao y duró tres años. Porque no me quería dejar mi hija y me ayudó, y él de soldao en la revolución esa de los japoneses.

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

«Yo trabajaba en un rancho día y noche. Antes de morir Marcelino y tuve que irme a trabajar, tenía muchas gallinas y pollitos, tenía todos reunidos. Los pájaros los tenía en jaulas y había veces que tenía chonte y otros gorriones, pero cuando ya no tuve tiempo, ya no tuve nada, ya na más que trabajar. Tenía que salir, porque dice el dicho que: «La carga hace andar al burro.» Sí. Sabe que cuando entré aquí me ayudaban con comida, con ropa, pero con dinero no. De modo que yo salí a trabajar y ganaba un peso por día. Y había veces que en el azadón, el desaique limpiando algodón, y ahí donde trabajé en ese rancho habían muchas flores. El trabajo era todo sentao, una se sentaba en botes, pero muy calientes estos botes, sobre todo en tiempo de calor. Se calentaban tanto y estaban muy fuertes, yo trabajaba en aquellas matas, y luego les quitaba el botón y las dejaba lo grande. Y luego se caminaba hasta otro, y así. Éramos muchas mujeres, 20 trabajando y ahí me ayudé mucho. Y de modo que cuando el señor tenía su rancho, agarraba muchos mojaos de Juárez. Porque allí está cerquita, y a los de Juárez los perseguía, los estos de federales, pero él los agarraba. Y trabajaban en el rancho.

«Luego ya me cambié yo, porque ahí en Texas tenía dos lotes que me había dao mi hermano y me cambié. Me cambié a mi terrenito, porque me dijeron que un señor me iba a hacer un cuarto. Pues era mi compadre para que no me molestara con mi marido.

«Cuando asistía pues no trabajaba, yo hacía la comida, hacía frijoles, huevos, tortillas y galletas. Me ayudaba mucho con eso y también había molino y hacía tortillas de masa. Las hacía a mano y las de harina con el palote. Así. (Isabel señala con la mano y se ríe mucho) Se amasa la harina y luego se hace pasteles con los palotes, después se pone la tortilla en el camal. Mire, este es el comal y éste es el palote y luego con eso hago todo. (Muestra en la cocina cómo se hace) Y hacía muchas cuando estaba en el rancho. A veces iban también los americanos, esos grandotes, iban a pie, esos que los llamábamos trampas, unos hombres grandotes y llegaban adonde hubiera comida. Cuando les pegaba el hambre. Ellos no sabían hablar español, puro inglés, y allí los de México creo que algunos sabían el inglés, de modo que pa pedíle de comer a usted decía así, y tenían hambre. (Isabel se pone la mano en el estómago, dándose palmaditas.) Sí, si, esta era la forma en que pedían de comer y respondíamos que había tortillas. Y les daba la comida que tuviera, pensaba que, pobrecitos. Y también en México, recuerdo que mi papá era muy bueno y había veces que hasta se quedaban allí en la casa, en la sala y ya le dije a mi mamá: «A esos hombres tan grandes, hasta miedo me dan.» Pero se acostaban allí y en la sala dormían. Y muchas comidas hacíamos.

«Como le había dicho, yo trabajé en ese rancho por quince años o más. Pero mi hija vivía aquí en California, y mi hijo político me decía que me viniera con ellos a vivir aquí. Me enviaron dinero y vine. Otra vez estaba aquí con mis niños. Yo era feliz en mi trabajo y mi vida fue mejor, más completa.»

Photography by Patricia Bolfing – Half Moon Bay (California)

Reminiscencias

«Muchas cosas han pasado en mi vida. Muchas cosas, toda mi vida. Ahí tengo la carta de mi mamá, ella murió cuando yo estaba en Texas. Y no la volví a ver más. Yo quería ir pero no fue posible porque estaba la Revolución de los Cristeros, ellos eran muy malos, todos. Eso no lo pasé yo, pero me platicó una señora amiga mía, que se llama María. Yo quería ir, pero mi hermano me aconsejó que estaba muy malo el camino y no fui. Tumbaban los trenes y era muy peligroso andar por allí. Muchas cosas me pasaron toda mi vida, muchas.»

María Jiménez cuanto lo sucedido en esta revolución de los Cristeros que ella si vivió. María es amiga de Isabel y se reúnen a platicar muchas veces. María visita a Isabel con frecuencia, siente cariño, amistad por Isabel. María vivió en México durante esta revolución, todavía viva en el recuerdo de muchos mexicanos. Su experiencia de terror y brutalidad manifestado en las tropas del gobierno es algo que María no puede borrar de su mente. Sin embargo en los dos lados se cometieron atrocidades. La historia que María cuenta es un lado nada más, una parte muy parecida a las historias que Isabel cuenta acerca de los Carrancistas.

«Los del gobierno eran los guardias. Los de la Iglesia eran los cristeros.» * Los cristeros eran buenos, los guardias eran malos. Plutarco Elías Calles, era yerno de Obregón y eran muy malos, él y los que iban con él. También el General Domínguez era muy malo, mataba a todo el mundo. Toda la gente estaba escondida. Yo tenía un vecino chamaco y lo tiraron, y le sacaron las tripas y dicen , que iba corriendo y murió. Encontraban las bestias heridas y muertas. Yo estaba recién casada. (Dice María)

«Decían también que iban a pasar a los ranchos los del gobierno, y no lo creíamos, pero así fue, pasaron. Mataron a gente muy buena y a todo el que encontraban lo mataban. No había que dejarse ver, había que tener mucho cuidado. Estábamos escondidos y oíamos el clarín. Un padre lloraba y se llamaba Secundino Bautista, era de La Palma Real, en Michoacán. Duró desde 1925 hasta 1929. Los cristeros estaban a favor de nosotros.